An assembly line in a Chinese electric three-wheeler factory. China produces hundreds of thousands of electric rickshaws annually for domestic use and export, dominating the global supply of these affordable EVs.

Introduction

In 2025, sweeping new U.S. tariff policies proposed by former President Donald Trump threaten to upend global trade – and one unexpected victim could be the humble electric rickshaw. These three-wheeled electric tuk-tuks, ubiquitous in Asian cities and now making inroads worldwide, face a radically altered market if steep tariffs take effect. This blog will explore how Trump’s 2025 tariffs might impact Chinese electric rickshaw exports to the West, and how leading manufacturers like QSD (Xianghe Qiangsheng) are responding through market diversification, localizing production, tweaking supply chains, and adjusting prices. We’ll also consider the broader implications for trade, manufacturing, and competitiveness in the electric three-wheeler sector in an increasingly protectionist era.

Trump’s 2025 Tariff Policies: A New Trade Barrier

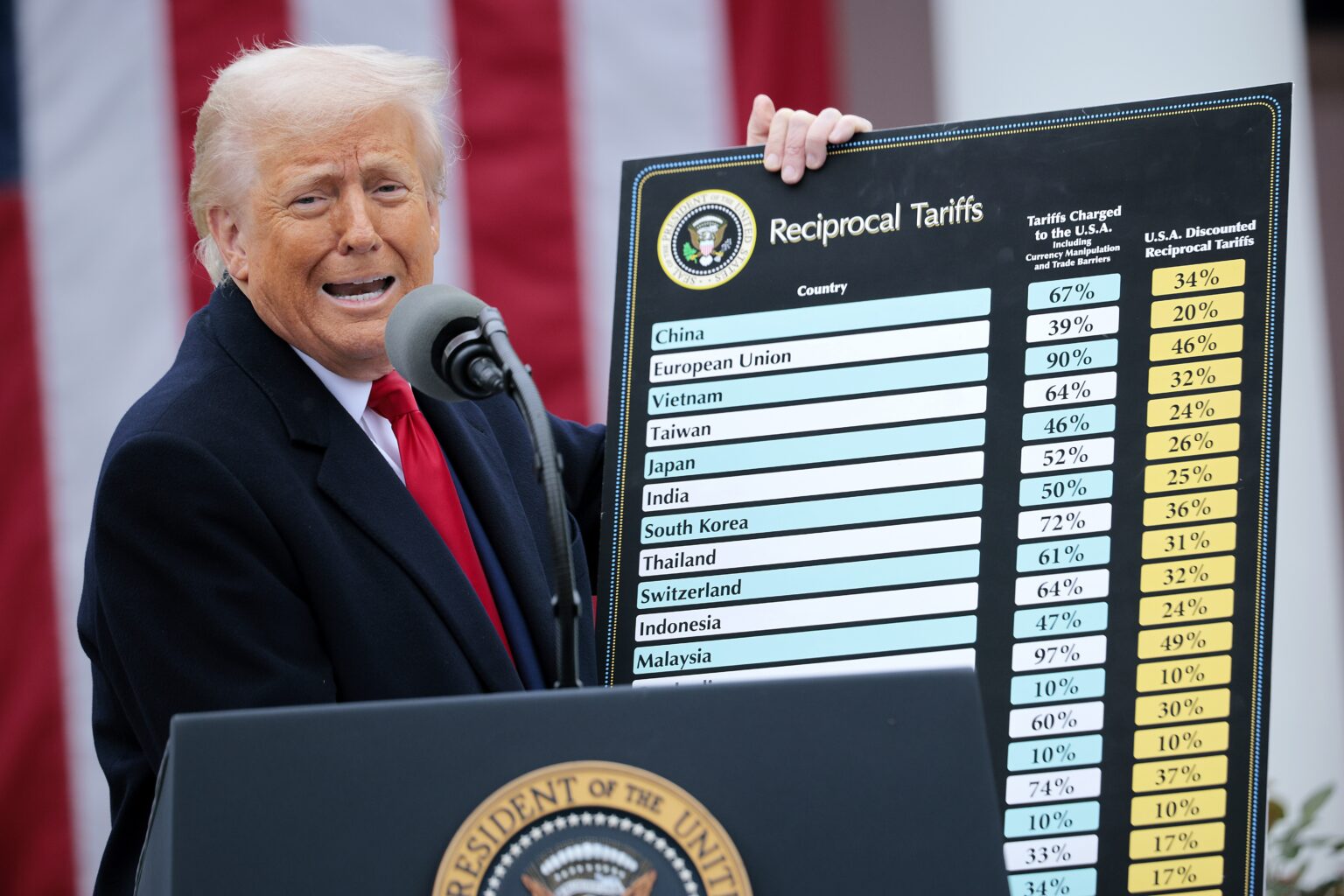

Trump’s second-term trade agenda in 2025 revolves around “reciprocal tariffs” – imposing high import duties to match other countries’ trade barriers

. In early April 2025, the White House announced a minimum 10% tariff on nearly all imports, with much higher rates for specific countries. China, in particular, was hit hardest: President Trump ordered an additional 34% duty on Chinese goods on top of an existing 20%, bringing total tariffs on Chinese imports to roughly 54%. This fulfills Trump’s campaign threat of punishing China with “worst-case” tariffs approaching 60%, justified as retaliation for China’s own trade practices.

Notably, electric vehicles (EVs) were singled out for even tougher measures. The U.S. Trade Representative conducted a special review of Chinese EV subsidies, after which the administration moved to slap a 100% Section 301 tariff on Chinese electric vehicles in mid-2024

. This enormous levy – effectively doubling the cost of imported Chinese EVs – was implemented under U.S. law citing China’s “unfair trade practices” in flooding markets with cheap, subsidized electric cars

. By 2025, the Trump administration signaled it would keep this 102.5% total tariff on Chinese EVs (100% penalty plus the standard 2.5% auto duty) in place

. In parallel, a new 25% tariff on all foreign auto imports (cars, trucks and likely electric vehicles) was announced in late March 2025

. This across-the-board auto tariff, effective April 3, aimed to protect U.S. automotive jobs but also threatened to raise vehicle prices by thousands of dollars and dampen demand, according to industry analysts.

For electric rickshaws – which fall somewhere between motorcycles and autos – these tariff policies create a daunting scenario. If classified under general Chinese imports, an e-rickshaw from China now faces around 54% U.S. import duty. If it’s treated as an electric vehicle (as many are battery-powered), it could even be subject to the punitive 100% EV tariff. And as a finished motor vehicle, it wouldn’t escape the new 25% auto import levy either. In short, Chinese-made electric rickshaws headed for the U.S. could encounter cumulative tariffs well above 50%, a crippling cost increase.

Nor is the United States alone. Other Western markets are also erecting barriers against Chinese electric vehicles. In Europe, the EU concluded an inquiry into China’s EV subsidies in late 2024 and announced new countervailing duties ranging from 17% up to 35.3% on imports of Chinese electric cars. Even Canada jumped in, mirroring the U.S. hard line – Ottawa unveiled its own 100% tariff on Chinese EVs in August 2024, citing China’s “non-market practices”

. Although these Western measures mainly target passenger cars, the broader stance signals a hostile environment for any Chinese electric vehicles, including three-wheelers, entering North America or Europe.

In summary, by 2025 the geopolitical trade winds have shifted sharply. Chinese exports of all stripes face higher hurdles, but electric vehicles are in a particularly precarious position. The stage is set for significant fallout in niche sectors like electric rickshaws, where China happens to be the dominant supplier.

Fallout for Chinese Electric Rickshaw Exports

China today utterly dominates the global electric rickshaw (three-wheeler EV) industry, so any trade shock to Chinese exports will reverberate globally. In 2024 alone, China exported around 650,000 electric tricycles (rickshaws) worldwide – an export volume worth nearly $5.5 billion USD, up ~10% year-on-year. These zippy three-wheelers have been spreading from their home markets in Asia to regions as far afield as Africa, Latin America, and even pockets of Europe and North America. Chinese models are popular for their affordability and simple design, used as short-distance taxis, cargo carriers, and personal transport in many developing countries.

Before the tariff announcements, Western interest in e-rickshaws was actually on the rise. Market projections in mid-2024 foresaw that while India and China would remain the largest e-rickshaw markets, certain Western countries (Spain, France, Italy) were poised for significant growth in this segment – with anticipated annual growth rates around 20–24% through 2034. In the United States too, social media buzz was building after viral videos showed Chinese electric tuk-tuks cruising American streets, astonishing onlookers with their novelty and utility

. U.S. consumers had begun ordering Chinese e-rickshaws online in small numbers, and Chinese “sanbengzi” (tri-bike) even got a shout-out from Chinese diplomats on Twitter for gaining popularity abroad. In short, the global electric three-wheeler was just starting to gain traction beyond its usual markets.

The new tariffs threaten to slam the brakes on this expansion, especially into the U.S. and Europe. Price competitiveness – the Chinese e-rickshaw’s key advantage – would be severely undermined. These vehicles are inexpensive by design (as low as ~$600 wholesale for a basic model), but a 50%+ duty at the U.S. border would jack up the cost for importers and consumers dramatically. A $2,000 rickshaw could effectively cost $3,000–$4,000 after tariffs – not even counting shipping and distributor mark-ups. In fact, even before the latest tariffs, the few Chinese three-wheelers available via import into the U.S. were retailing at $5,000–$12,000 each due to freight, fees and limited supply

Chinese manufacturers also face the headache of tariff-related uncertainty and compliance. The overlapping U.S. measures create confusion about how an electric rickshaw would be classified and taxed. Is it a “motorcycle,” an “auto,” an “electric vehicle,” or just a generic Chinese commodity? Depending on the classification, different tariff rates (10%, 25%, 54%, 100%…) might apply. Navigating this can be risky – a misclassified shipment could incur hefty back-duties or even be turned away. This uncertainty alone could dissuade Chinese companies from attempting to ship into the U.S. at all, at least until there’s clarity. The EU’s new subsidy tariffs similarly mean that any Chinese e-rickshaw perceived as subsidized could get hit with ~20–30% duties at European ports.

All of this amounts to a significant loss of market opportunity for China’s e-rickshaw exporters in the West. While the U.S. and Western Europe are not (yet) major consumers of three-wheelers, they were seen as frontier growth markets – places where electrified micro-mobility could take off with environmental and urban mobility trends. If Chinese companies are priced out by tariffs, those opportunities might be seized by others (perhaps local Western startups or Indian exporters), or the market might simply remain underdeveloped. For the Chinese firms that have ridden a wave of global demand – recall that China’s export of electric tricycles grew to 650k units in 2024– this is an unwelcome roadblock. It comes just as many had ramped up production capacity expecting overseas growth. In the words of one Chinese manufacturer, overseas orders had “surged” and 2024 was a “golden opportunity” thanks to global interest in low-carbon vehicles. That boom could turn to bust in certain regions if sky-high tariffs cut off access.

There may be a silver lining for some competitors outside China. India, for example, has a large domestic e-rickshaw industry and could potentially fill some of the gap in Western markets if Chinese products face barriers. Indian-made e-rickshaws might not incur the extra China-specific tariffs (though they’d still face the baseline 10% U.S. import tariff and have to meet safety standards). However, Indian exporters themselves are few and haven’t strongly targeted the West yet. Another possibility is Western manufacturers (or importers) seeing an opening to produce these vehicles locally. Yet, given the low price point and simple technology of rickshaws, Western firms would struggle with labor costs and economies of scale to compete on price – the very reason Chinese models dominated in the first place.

In essence, the immediate impact of Trump’s 2025 tariffs on the electric rickshaw sector is a likely drop in Chinese exports to the U.S. and EU, accompanied by higher prices and reshuffling of sourcing. Chinese producers will be forced to adapt or cede those markets. Below, we examine how leading companies like QSD and peers are responding to this challenge.

How Chinese E-Rickshaw Companies Are Responding

Chinese electric three-wheeler companies are not standing idle in the face of new trade barriers. Many of the leading manufacturers – including QSD (Xianghe Qiangsheng), Jinpeng, Yadea, and others – learned hard lessons from the U.S.-China trade war of 2018–2020 and have been proactively adjusting their strategies. The playbook for surviving tariffs includes diversifying into new markets, localizing production overseas, tweaking supply chains, and adjusting pricing strategies. Let’s break down these responses:

1. Market Diversification: Finding Friendly Shores. Chinese e-rickshaw exporters are aggressively diversifying their market focus away from tariff-hostile countries. Instead of relying on the U.S. or Western Europe, they are doubling down on demand in South Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America, where tariffs are lower and sales are growing. For example, Bangladesh – which until recently had banned electric rickshaws – is now legalizing and regulating them, potentially opening a huge market of 2–4 million vehicles operating on its roads. Chinese brands like QSD see such developments as chances to expand sales in Asia without tariff worries. Africa is another frontier: many African nations are hungry for affordable transport and have little local manufacturing, making them natural destinations for Chinese EV tricycles. By spreading exports across dozens of emerging markets, companies can cushion the loss of any one region. QSD (Qiangsheng) exemplifies this approach – it built a “stable supply chain in Asia, Middle East, Africa, South America, Australia, Europe and India” by 2013, selling to over 100 countries. This broad base means even if the U.S. market closes, a firm like QSD still has plenty of customers elsewhere. In fact, many Chinese e-tricycle makers now report overseas sales in 140+ countries and regions, a truly global footprint. These firms attend international trade shows and “venture abroad in groups” to promote their brands beyond just the West. So, while tariffs might shut one door, Chinese electric rickshaw makers are busy opening many others.

2. Localizing Production Overseas: Beating Tariffs by “Made-in-XX”. A powerful long-term response is building assembly plants or partnerships in the target markets to bypass import tariffs. If the rickshaw is assembled in, say, Mexico or Indonesia instead of China, it may avoid the punitive China-specific duties. We are seeing Chinese companies actively pursue this strategy. Several major electric two- and three-wheeler manufacturers from China have opened factories in Southeast Asia – a region with free trade agreements and close proximity to key markets. For instance, Yadea (a top e-scooter and e-trike maker) and a company called ZXMCO have established production bases in Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines recently.

By producing there, they can export to the West under those countries’ names, often tariff-free or with lower rates. Plans are underway to set up production bases in Europe as well, with multiple Chinese “tri-bike” makers exploring assembly facilities within the EU. Building inside Europe would allow them to label the rickshaws “Made in EU” and avoid the EU’s anti-China duties, while also being closer to customers. This mirrors what happened after earlier U.S. tariffs: Chinese bicycle manufacturers moved final assembly to places like Taiwan, Vietnam, and Cambodia to dodge Trump’s 2018 tariffs. In effect, Chinese firms create overseas subsidiaries or joint ventures that import knock-down kits of parts and assemble the finished vehicles locally. The Ministry of Commerce in China noted that due to varying regional requirements, some e-tricycle companies had already “established factories overseas to carry out targeted production and R&D” by early 2025. Leading player QSD, for example, could partner with local entrepreneurs in Africa to assemble its rickshaws there, eliminating the tariff cost and even gaining a “made locally” marketing edge. This trend of Chinese manufacturers becoming multinational producers is accelerating because of the tariffs – a clear case of tariffs “pushing factories into other countries” rather than back to the U.S..

3. Shifting Supply Chains and Component Sourcing: Even when final assembly can’t be moved, Chinese firms are tweaking their supply chains to minimize tariff exposure. One tactic is to source more parts from neutral countries. For example, a rickshaw maker might start buying batteries from South Korea or motors from Thailand instead of China, so that the finished vehicle contains less “Chinese-origin” content. If done cleverly, the product might qualify as originating from a third country under trade rules, thus evading China-specific duties. Another tactic is routing products through countries with trade agreements. Some Chinese companies export semi-finished rickshaw kits to nations like India or Mexico for further processing, hoping the product’s origin can be partly attributed to those countries. However, such maneuvers must satisfy rules-of-origin tests (often 50%+ local value-add) to truly escape tariffs – not easy for a primarily Chinese-made good. Still, we have seen creativity here: Chinese exporters have used entrepôt countries (e.g. Malaysia, Vietnam) as springboards to the U.S., effectively laundering the origin of goods. This was evidenced by the bike industry example where Chinese firms set up assembly in multiple ASEAN nations to avoid a straight-from-China label. Electric rickshaw makers can follow suit, since the assembly of a three-wheeler is relatively low-tech (it “can be done in as fast as 10 minutes” on an optimized line). In addition, companies are investing in R&D to tailor products to each region’s standards

– this isn’t a direct tariff dodge, but it ensures that if they do assemble in Europe or America, the vehicles meet local regulations and can be sold legally, maximizing the benefit of local production. The net effect of these supply chain shifts is a further globalization of the production process – ironically achieving the opposite of the tariffs’ intent (which was to reshore manufacturing to the U.S.). As one industry CEO observed, Chinese factories just end up “setting up in other countries” and continue exporting, albeit with extra logistical costs.

4. Price Adjustments and Absorbing Costs: When all else fails, companies confront a tough choice – raise prices and potentially lose sales, or eat the cost increases and sacrifice margin. With tariffs of the magnitude we’re discussing, fully absorbing them is usually impossible (a 50% duty could wipe out any profit). However, firms can make selective adjustments. Some Chinese exporters might offer discounts or cut their margins to keep delivered prices low in critical markets, at least temporarily. For instance, if a rickshaw normally sells to a U.S. distributor at $1,500, the Chinese exporter might agree to drop it to $1,100, softening the blow of the tariff-added cost on the final retail price. Large manufacturers with deeper financial reserves are more able to do this than smaller ones. In many cases though, the additional tariff cost will be passed on to consumers, as Magna International’s CEO bluntly noted when facing Trump’s auto tariffs: “there’s no easy way to absorb this” – much of the cost gets added to the vehicle price for end buyers. Indeed, U.S. importers of Chinese e-bikes during the last tariff round had to raise retail prices by an estimated $300–$500 per unit to cover the 25% duties. We can expect a similar dynamic with e-rickshaws: prices in the West would rise, and sales volumes likely fall correspondingly. Chinese firms may try smaller cost-saving measures to offset tariffs – for example, using slightly cheaper components, or streamlining packaging/shipping to cut freight costs – but these yield only marginal savings. In some cases, Chinese companies might choose to prioritize higher-end models or value-added versions in tariff markets, reasoning that a wealthier niche clientele can bear the higher prices. They might market their product as a premium, novelty EV in the U.S. (where a few thousand dollars extra is acceptable for a fun gadget) while reserving their mass-market cheap models for non-tariff markets. This kind of segmentation is a form of price strategy too. Overall, expect some combination of modest price hikes and margin compression. However, if tariffs stay high long-term, the only sustainable solution for Chinese firms is likely the earlier points – relocating production or exiting the market – because continuously selling at a loss is not viable.

In summary, leading electric rickshaw companies like QSD are actively deploying a mix of these tactics. QSD has presumably expanded into regions like Africa and South Asia to grow sales where tariffs aren’t an issue (diversification). It has the technical capacity to set up assembly abroad – Chinese reports indicate e-rickshaw makers from Jiangsu and Henan provinces have already built plants overseas or are planning to– so QSD could do the same in strategic locations. Supply chain flexibility is in their DNA; they can source parts globally if needed. And while no company welcomes shrinking profits, the more established players can tolerate short-term hits to maintain market presence. Flexibility is key, as one CEO emphasized, in navigating these “uncontrollable” tariff shocks. The electric three-wheeler industry in China is showing flexibility in spades by rapidly recalibrating its global strategy.

Broader Implications for Trade, Manufacturing, and Competitiveness

The tussle over electric rickshaws is a microcosm of larger trends in global trade and manufacturing in 2025. Trump’s tariff salvos and the responses of Chinese firms illuminate the following broader implications:

-

Acceleration of Supply Chain Realignment: Trade barriers are turbo-charging the decoupling and re-routing of supply chains. We see Chinese EV producers moving production to third countries, which is part of a wider realignment where manufacturing shifts to circumvent tariffs. This echoes what happened in other sectors – e.g., electronics and appliances – during the trade war. In the EV space, it means the global supply chain becomes more geographically distributed. Southeast Asia, South Asia, and others become bigger manufacturing hubs as China’s direct exports to the West decline. Tariffs intended to hurt China may succeed in reducing “Made in China” labels on final goods, but the production often still involves Chinese companies operating behind the scenes in other locales. The electric three-wheeler industry could see a network of assembly plants spanning Asia/Africa, coordinated by Chinese parent firms. This dilutes China’s onshore manufacturing advantage somewhat, but also spreads technology and investment to other developing economies.

-

Limited Repatriation of Western Manufacturing: One goal of tariffs is to bring manufacturing jobs back to the U.S. or Europe. In the case of e-rickshaws (and many similar products), this appears unlikely to happen at scale. The production of these vehicles is low-cost and labor-intensive – moving it to high-wage economies defeats the cost proposition. The experience from bicycles and other consumer goods shows that instead of sparking U.S. factory rebirth, tariffs led to production moving to other low-cost countries or companies absorbing costs with minimal U.S. job gains. For e-rickshaws, Western manufacturers might not suddenly emerge to build tens of thousands of units domestically, because the market is still too small and the economics unfavorable. Thus, the tariff may protect hypothetical U.S. producers that don’t yet exist, while inconveniencing existing Chinese producers and raising prices for consumers. As one industry voice said about the earlier tariffs, “there’s no real gain here… it’s very inflationary”. So broader implication: tariffs can be a blunt tool that redistributes manufacturing among offshore locations without significantly boosting domestic output – a pattern likely to hold in the EV rickshaw segment.

-

Trade Tensions Spilling into Green Technology: The electric rickshaw story shows that green transport technologies are not immune to geopolitical trade fights. In fact, they are becoming a central front. EVs, batteries, solar panels, etc., are all seeing tariffs and counter-tariffs. This could have a chilling effect on the adoption of clean vehicles globally, as costs rise due to tariffs. If e-rickshaws become pricier in some countries, that might slow down the transition away from polluting diesel three-wheelers. More broadly, it signals a world where each bloc wants its own EV supply chain (U.S., Europe, China each internalizing production). The competitiveness of the electric three-wheeler sector will partly depend on how efficiently companies can navigate these fractured trade blocs. Those that adapt (like by localizing assembly in each region) will stay competitive; those that don’t may lose out. Over time, we might see a more fragmented market – Chinese-made rickshaws dominating Asia/Africa, but European-made ones serving Europe, and perhaps U.S.-made niche models in America, since free trade can no longer be taken for granted.

-

Innovation and Upgrading as a Response: A positive side-effect is that Chinese manufacturers, to justify their presence in tariffed markets, might focus on innovation, quality and branding. When you can’t win purely on lowest cost (because tariffs erased that edge), you invest in making a superior product that consumers are willing to pay a premium for. The Xinhua report noted that Chinese EV firms are shedding the old image of “cheap and low-end” and incorporating more advanced technology and better quality control, which overseas buyers are noticing. QSD and peers might accelerate development of higher-performance e-rickshaws – longer-range batteries, safer designs, smarter features – to differentiate themselves. This could raise the overall competitiveness of electric three-wheelers as they evolve from basic carts to more sophisticated micro-EVs. In other words, tariffs can push companies to climb the value chain. We may eventually see Chinese-made three-wheelers that, even after tariffs, find buyers because they’re uniquely good (just as some high-end Chinese drones or appliances still sell despite tariffs due to quality). Competitors in other countries will likewise need to up their game technologically to compete.

-

Potential Shake-ups in Market Leadership: If Chinese exports are constrained, other players could gain ground. This might be an opportunity for Indian manufacturers to try exporting e-rickshaws (India has a vibrant domestic industry with firms like Mahindra Electric, Kinetic Green, etc.). Similarly, companies in Thailand or Vietnam could step up – Thailand already has expertise with tuk-tuks and might develop its own electric versions for export. The competitive landscape in the electric three-wheeler sector could thus broaden. While China is far ahead now, prolonged trade barriers could seed alternative hubs. In the long run, this might lead to more balanced global competition, which can spur further innovation and possibly drive down costs once multiple countries produce at scale. However, in the near term (next 1-3 years), China’s incumbents have a huge volume and cost advantage that won’t be quickly matched. They’ll likely remain dominant, albeit forced to operate via overseas branches or partnerships.

-

Trade Negotiations and Policy Uncertainty: The situation also underscores the importance of international trade negotiations for niche industries. If diplomatic tides change (e.g. a future U.S. administration rolling back some tariffs or making a deal with China), it could suddenly reopen markets. Companies have to remain agile and hedge their bets. For now, Chinese firms assume high tariffs are here to stay and plan accordingly, but they’ll also be watching for any easing. The unpredictability of policies (“policy uncertainty”) is itself a challenge – firms must make investment decisions (build a factory abroad or not?) under unclear timelines for how long tariffs will last. This is a broader issue affecting many sectors beyond e-rickshaws: the instability of trade rules can inhibit long-term planning and capital expenditure. Many auto industry leaders lament that constant upheaval in tariff regimes makes it hard to have “certainty and stability” for manufacturing and supply chain decisions.

Conclusion

The saga of Trump’s 2025 tariffs and the electric rickshaw industry highlights the intricate interplay between geopolitics and green technology markets. On one hand, we have a thriving global electric three-wheeler sector – epitomized by Chinese firms like QSD – that has been driving costs down and spreading clean mobility to new corners of the world. On the other, we have a resurgence of protectionism and trade barriers that threaten to fragment that global market and raise prices. Chinese electric rickshaws, which until recently were winning over consumers overseas with unbeatable value, must now navigate a maze of tariffs to reach those customers.

The response of the industry has been telling: rather than capitulate, companies are swiftly adapting through diversification of markets, overseas production, supply chain rerouting, and pricing maneuvers. These moves will allow many to weather the storm, albeit at some cost. We’re likely to see Chinese-made e-rickshaws continue rolling on streets from Dhaka to Nairobi to Lima – and even in New York or Paris, though perhaps delivered via a detour in Vietnam or Turkey to sidestep tariffs. The electric three-wheeler sector may become a more regionally split industry, but it is not likely to disappear from global trade. If anything, the contest will spur players to become more efficient and innovative.

For policymakers, the electric rickshaw is a small piece of a much larger puzzle about how to balance national interests with global climate and development goals. High tariffs on these vehicles protect certain industries, but they also risk slowing the adoption of a clean transport solution in cities that could benefit from them. It’s a reminder that trade policy can have unintended side effects on sustainability.

As for competitiveness, China’s current lead in this niche will be tested. Companies like QSD, with their extensive experience and scale, have the best shot at maintaining dominance by evolving into true multinationals – essentially outmaneuvering tariffs. New challengers may emerge in other countries, but they will need to match China’s combination of affordability, quality, and adaptability that has won over so many buyers. The race is on to see whether tariffs merely shift the “Made in China” label to “Made in Vietnam” (with China still pulling the strings), or whether they genuinely level the playing field for other nations to compete in the electric rickshaw space.

In conclusion, Trump’s 2025 tariff gambit is reshaping the global electric rickshaw industry, but it is far from derailing it. The sector’s supply chains are reconfiguring, its market map is being redrawn, and its leading companies are adapting with resilience. For the electric three-wheeler, as with many things, necessity is the mother of reinvention. The coming years will reveal how a small but significant EV industry transforms in response to big geopolitical headwinds – and whether the iconic electric tuk-tuk can keep on trucking (quietly) into a greener future despite the bumps on the road.

Post time: Apr-03-2025